When the United States began its formal military withdraw from Afghanistan in August, active-duty service members in that region weren’t the only ones to respond with swift action.

On the home front, James Taylor mobilized his counseling skills to lead weekly virtual group therapy sessions to support student veterans at CSN and UNLV, especially those who served in the Middle East.

Taylor, a licensed clinical social worker and former U.S. Marine, is a new addition to both institutions in a role fully funded and coordinated by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

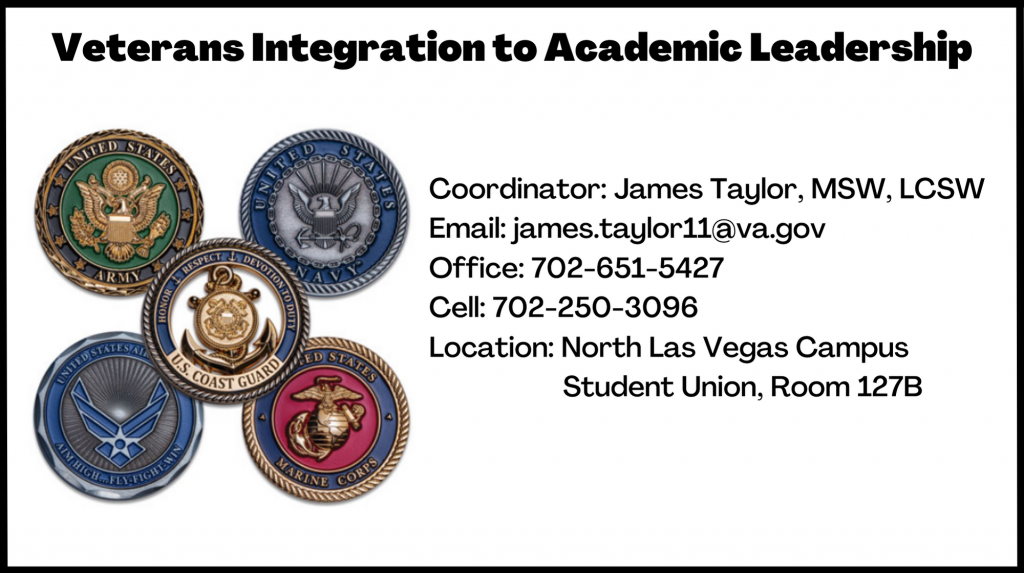

This summer, the VA installed Taylor as the sole Southern Nevada coordinator for the Veterans Integration to Academic Leadership (VITAL) program—a program to enhance veterans’ retention and holistic success through campus–community initiatives; provide on-campus clinical care and coordination; and collaborate with the VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System, Veterans Benefits Administration, as well as faculty, staff and community resources.

Taylor’s chief responsibilities involve helping student veterans bridge complex VA services that include the military-to-college transition and access to healthcare, with an emphasis on no-diagnosis-required mental health assistance.

In fact, his recent group therapy sessions, spanning about two months altogether, were an anticipatory response to the mental health challenges many veterans face when transitioning from military to civilian life. Taylor said the individuals who attended the sessions were interactive and reported feeling less stress afterward.

That initial sense of post-military service ambiguity resonates with Taylor.

After completing his U.S. Marine Corps enlistment obligation, he enrolled in college and experienced numerous difficulties, such as not knowing where to go for the right information or understanding his GI Bill funding.

“I assumed if I couldn’t figure college out on my own, I shouldn’t really be there,” said Taylor, who dropped out and reenlisted in the military—a culture of support he understood—before eventually returning to college to complete bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

“If there had been a VITAL program at that time, I could have learned how to manage my own concerns, as well as been connected to the right programming and people to improve my ability to be successful,” Taylor said.

As one of about 135 VITAL program coordinators across the country, Taylor is now in a position to extend lifelines of support, whether through his counseling interventions, training sessions or referrals to VA, college and community resources.

“When people are struggling to manage their current life situation, adding extra layers to get help makes it less likely they will pursue what they need,” Taylor said. “Providing services where there’s a veteran—a person they can come to rather than call an 800 number—will drastically improve the likelihood of them pursuing what they need.”

The VITAL program will be a strategic partner with CSN’s Veterans Education and Transition Services, said Vanessa Winn, assistant director for VETS. She named veterans’ mental health awareness, suicide prevention and general VETS event collaborations as short-term goals, and permanent connections to VA physical and mental healthcare resources as long-term ones.

Winn added that student veterans bring several qualities to the classroom and college community with their presence and participation.

“First, they offer a unique perspective to share with classmates and instructors during classroom discussions,” Winn said. “Second, there is a certain determination gained from the trials and tribulations many face during the high-stress moments that are hallmarks of military service. Often, these experiences can place them in spots to be an example for the rest of the student body.”